Designing and composing for print is, relatively, easy. Choose your output size – A5, Double Royal, 48-sheet, whatever – and what you design is what the reader sees. Doing the same for screen, however, is much more difficult. I’ll come back to websites another time, but I haven’t finished with video yet. Dear me, no.

Back in the day, television screens were in the ratio 4:3. Cinema formats could vary, and some were very wide indeed, but the compromise widescreen TV format is 16:9. There’s also an intermediate size, 14:9, which tries to bridge the gap. Mostly, broadcasters will zoom in (cropping heads in close-ups) or stretch the 4:3 original in order to fill the screen. Sometimes it’ll be the viewer who does this, because why pay for a widescreen TV when it isn’t full of actual picture?

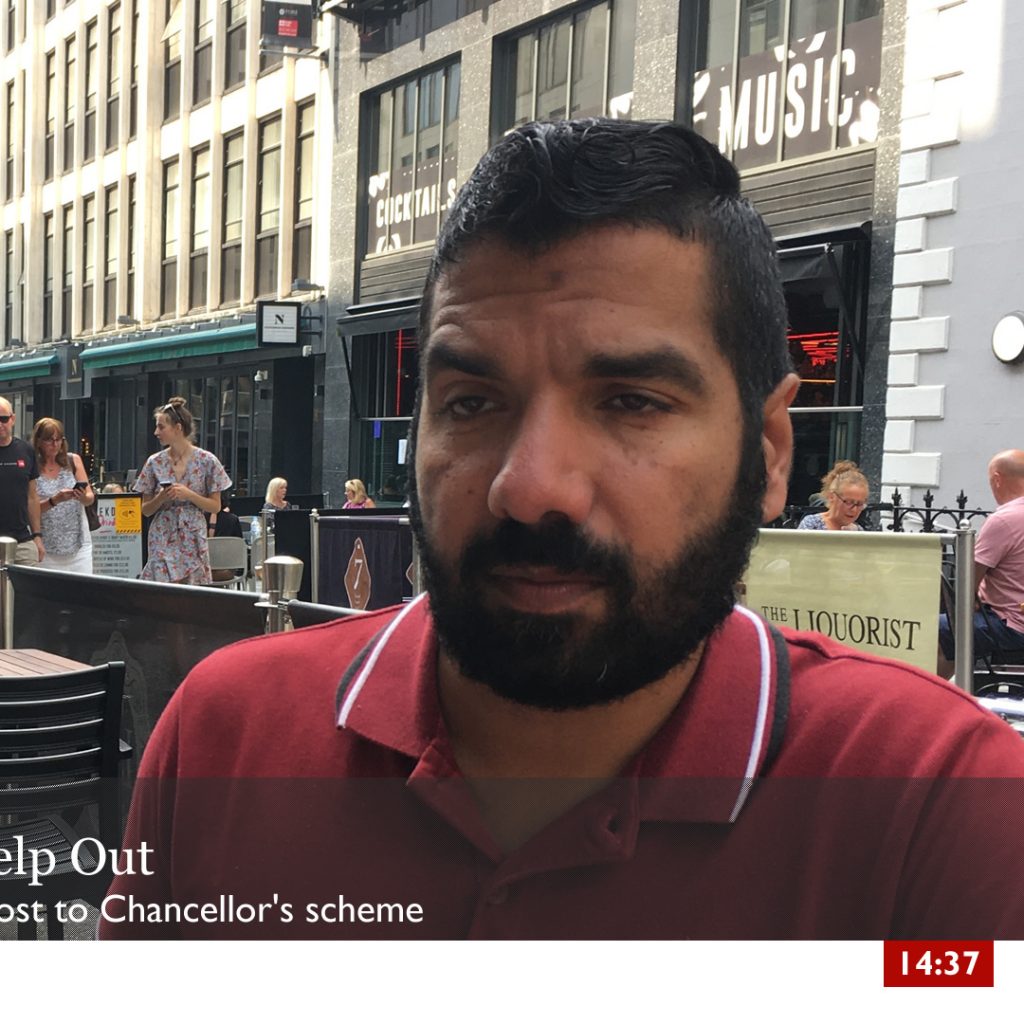

The BBC in particular has what’s called the safe area (although most broadcasters do the same for new material – go do some research). Compose the shot for 16:9, but make sure that all the important stuff – such as your interviewee in a news programme – is in the 4:3 area. Expensive video cameras will have markings on the viewfinder to help the cameraperson frame the shot correctly. And if you add any captions or titles, put them in the 4:3 safe area.

Why you should care

Sometimes it’s called B-Roll, sometimes archive or stock footage, but we’ve all seen those shots of trains running through stations, ferries leaving harbour, students celebrating exam results and not for a moment thought that those shots were not filmed at the same time as the rest of the report.

It’s not always possible for broadcasters to film what they want, when they want. When I worked at Metro, for example, we’d never allowed video or radio onto our bus stations during the rush hours as they might interrupt normal operations (get in the way of passengers). Same with rail, but with even more safety rules: tripods were usually banned, and you had to stand a fair way back from the platform edge. And good luck with getting into Sellafield.

If you can’t afford to get in a professional crew but you do have a camera capable of shooting 16:9 1080p Full HD (1920 x 1080 pixels), or even 720p at a pinch, you can offer some stock footage to broadcasters who can’t physically get to you, or who can’t film when you want them to, or aren’t allowed anywhere near where they’d like to be.

In which case, it pays to know how to compose a shot. Things like track & pan are beyond the scope of this Thought though. Go on a course like I did1.

Channel You

In the previous post I alluded to a student group that had tried to be a bit too creative. They were filming a person talking and wanted some action in the background. Fine, but they filmed the speaker in a wide shot, pointing out of the frame. Compare the two images below; one by the students, one by me. One looks wrong, one looks right (or less wrong, anyway).

What does that mean? Well, watch the news tonight. Notice how the interviewee is off to one side of the screen, medium close-up (MCU in the jargon), still in the safe area and talking into the empty part of the screen? That’s talking into the frame. You always want to compose things this way, otherwise it looks a little… odd (see above). Again, I’ve mocked up a pseudo-BBC News graphic over an image of someone pretending to be interviewed so you get the idea.

Sometimes a sit-down interview is composed with the side or back of the head of the interviewer in shot. It usually depends on the interview topic and the location but the basic talking-into-the-frame composition holds.

Creativity is all well and good, but not if it distracts from the message.

Where it goes wrong

This is great for television. But what about mobile devices?

I’m writing this on a Windows 10 laptop with a 16:9 screen, but some screens are 16:10 (my much older laptop from 2005 was). The iPad Air and iPad Mini sat next to me are 4:3. My iPhone SE (2016) is 16:92.

Still photography? Usually 3:2, reflecting the original size of 35mm film. Digital SLRs use this ratio, although mobile device cameras use 4:3 – something to be aware of if you’re mixing and matching content.

Many Android-based phones come in at 2:1 (the same as the image at the top of this page), while Samsung phones are around 18.5:93. The latest iPhones are even wider than that (around 19.5:9), and who knows what the new iPhone 12s and similar will be?

There’s only one way to crop content to fit all screens, and irrespective of the portrait or landscape orientation of the device: 1:1 (square). Hurrah! Squares shall inherit the earth.

Except… Microsoft Video Editor doesn’t have a 1:1 option, just 16:9 and 4:3. iMovie on my iPad doesn’t have any aspect ratio change option, that I can see. That means you’re only option is to buy or subscribe to an app, and I’m just not going there.

Final thought

You know that user-generated content from volcanic eruptions, terrorist attacks, etc.? If you’ve the presence of mind to whip out your phone, why not turn it to landscape? Thanks.

- While I was a student, but in my spare time, in 1986. Very large cameras using low-band U-Matic tapes, huge edit systems that only worked if you’d remembered to give your recording an eight-second lead-in so that play and record machines could sync for speed. Happy days. [↩]

- Twenty Eight B: “Measuring up – reference table for iOS device dimensions”, https://28b.co.uk/ios-device-dimensions-reference-table/ [↩]

- Wikipedia: “Aspect ratio (image)”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aspect_ratio_(image) [↩]